November 2018

In a recent talk, Paul B. Preciado spoke of the political genealogy of museums and their importance as complete institutions, ones that are aligned with prisons, hospitals or schools in their work in favour of the normative production of subjectivity[1]. The museums we know today are the legacy of the countercultural revolution of the 1970s and subsequent decades of activism and institutional criticism of the museum-mausoleum. They strive to cease being spaces of the elites – the erstwhile bourgeoisie of the nineteenth century, spaces of heterocentric, white enunciation – that produce while legitimizing «our truth» as Western bearers of a privileged culture.

Moving nearer to our time, we see museums enter a new period marked by a «multicultural» mission in which a variety of actions are deployed to account for contemporary cultural and identity diversity so that they may be redeemed from the hegemonic colonial, erudite mandates from which they were born. For this reason, since the 1990s, exhibitions involving women, LGBTI + identities, artists from Africa, Asia or Latin America etc. have appeared on the agendas of the most renowned contemporary art museums. In parallel, educational departments, spaces traditionally intended for the reproduction of curatorial discourse and the indoctrination of audiences with the desire to become cultivated, experienced an unprecedented boom accompanied by the postmodern multicultural discourse. Education in museums thereby became, just like exhibitions, a device with which to activate this new museum paradigm: a device for acquisition, classification and programmatic specialization to attract diverse audiences, in a concept of banking and transactional[2] education that has no qualms in adopting the concept of mediation as a banner for this new postmodern contract between museums and citizens.

Museums, while claiming to give voice and place to others to whom they refer as publics, audiences, users or even clients, have in reality re-empowered themselves after decades of institutional and social discredit. They now exercise their authority by deploying strategies that are applauded by broad sectors, not only social and cultural ones but -and much more significantly- business. A host of activities for all types of public, selected and «sectioned» according to age, origin, (dis)ability, ethnic group, cultural interests and divided even by gender or sexual identity, are the new tactics of postmodern museums that assume in their proposals the commercialization, not only of the art object, but of the processes and experiences that they can provide.

This manner of understanding museums within their own political genealogy and situating the work of departments of education and cultural action today is necessary to encapsulate the work of the Laboratory of Experimental Audiovisual Anthropology, (Laboratorio de Antropología Audiovisual Experimental, Laav_). This space was formed to experience new ways of doing things; firstly, with people that break with the logic, on the one hand, of consumer hyperproduction, and, on the other, of postmodern cultural colonization.

Aware of the importance of museums as privileged social spaces, configurators of the public sphere, melting pots of diverse subjectivities and unexpected relationships, it was important that the ways of activating such potentialities were also in line with the project’s principles and objectives. Accordingly, the Laboratory aims for its practices to define it as a feminist space, one which advocates the celebration of diversity in terms of social and cultural justice but also the implementation of projects where people’s desire and interest takes precedence over the discursive outline that can propitiate an exhibition or a work. The Laboratory is therefore a social space in essence and this is crucial to understanding its experimental nature as a test tube for research.

Using the definitions of Almudena Hernando, the Laav_ is committed to a working method linked to «relational identity» as opposed to what is termed «individual identity», and which refers fundamentally to methods that pertain to patriarchy. Issues such as authorship, the concept of artwork as a product or the importance of exhibition circuits legitimized by the art system, are less important in the assessment of work than the ability to generate emotional bonds, relationships of trust and respect and the ability to resolve creatively and collectively the challenges that arise during the work process.

We can situate as precedents of Laav_ several prior experiences with collectives and chiefly a series of audiovisual workshops: I /We (2012-2015), which evolved into a community that is active at present, La Rara Troupe[3], which reflects in the first person on issues related to mental health, as an issue that affects society as a whole beyond diagnoses. This project has demonstrated throughout its development, from creative practice and associated research, the possibilities —and limitations —of autoethnography, the strategies to summon or gather everyone’s creative capacities, the need to work with inclusive groups, the importance of opening up the community to a network that regularly introduces new perspectives, and the diverse ways in which those of us who work in the museum institution can situate ourselves within those communities.

These experiences and learnings raised the possibility of creating Laav_ as a stable framework of action and thought in order to experiment and investigate collaborative practices with communities through audiovisual creation. In all cases, we understand our work to be a practice that is intrinsically linked to the community that makes it and that sets out in its design from the first-person plural. Beyond trying to use audiovisual language to illustrate or represent an aspect of reality, the aim is to employ it as a form of collective enunciation and creative, critical and transformative reflection that generates a new reality through the articulation of images and sounds in «a clash of cultures, voices, bodies and languages»[4]. Miguel Ángel Baixauli, in his profound analysis of Laav_, wrote:

If we think that knowing means to adequately represent what we suppose things are (our theoretical idea about them), we do not depart from Western metaphysics, from the projection of the intelligible model over the sensible, from meaning over the perceptible, from linguistic categories over what is real. If, instead, knowing means transforming what we think and transforming ourselves, then it is no longer a matter of representing anything, but of thinking differently, as Foucault would say, of going through an experience that transforms what we thought[5].

Audiovisual creation as a means to explore social issues about the human group that makes it becomes a practice which makes autoethnography from ourselves, which questions the notion of the other, an audiovisual anthropology based on trial and error, empirical and experimental, ever searching for new expressive possibilities, even if it does not disdain the paths already travelled by cinematic and anthropological tradition. David MacDougall warned of a non-questioning anthropology, one that is more interested in confirming what it already knows than in seeking «something quite different», in the face of what was proposed by the possibility of a «radical ethnography»[6]. Thus, the framework of the Laboratory arises naturally as a space in which experimentation and research go hand in hand when creating and generating embodied knowledge»[7]. It is about questioning and rethinking questions about representation, aesthetics and learning, as well as the ideas of community and identity. As Catherine Russell wrote, «autoethnography is a vehicle and a strategy for questioning imposed forms of identity and exploring the discursive possibilities of non-authentic subjectivities»[8].

One of the Laboratory’s essential approaches is the collaborative act, understood as a horizon towards which we are heading along different paths, none without its difficulty. Alain Bergala in The Cinema Hypothesis identifies an extreme difficulty with regard to this:

In the act of creating cinema, one of the greatest difficulties, and the cause of many failures, lies in the fact that despite it appearing to be collective work, there is only one person who has the film as a future whole in their head, although always in a rather blurred way and with poorly-defined areas. The fact that the shooting of a film mobilizes a team does not change anything in this regard: the centre of creation in the cinema is always an individual[9].

Bergala, while raising the impossibility of a truly collective cinema, targets the solution: will we be able to get a community to imagine a film? The key point would be to get the group to «have the film in their head». The generation and management of a common imaginary in something as elusive as an artistic creation is an essential task in collective processes. At the Laav_, we regard the creation process as also a process of discovery and shared learning. We might not have to be clear about a final result right from the start, but rather opt for an organic cinema that is discovered, collectively, on the path of creation. As Ignacio Agüero recalls, «Godard already did this from his first film, shooting and discovering cinema at the same time»[10]. This also incorporates one of the educational dimensions inherent in any process, learning from the practice itself.

Other difficulties entailed by collaborative creative practices relate to the knowledge and technical skills necessary to undertake them, which that raises the need for accompaniment by professionals or experts. Jay Ruby points out the consequent paradox:

Films with shared authority may be an impossibility. Collaboration requires participants to have some kind of technical, intellectual and cultural parity. If the subjects are recognized as filmmakers trained in collaboration, why would they need an outside person? Would they not want to make their own films?[11]

Again, the approach to the problem can provide the solution. Ruby talks about the professional who gives advice as an outsider. We at the Laav_ have chosen to try to expand the community so that it includes all of us who are undertaking the project, a community in which all the members have to learn from each other over a sustained period. Therefore, we would be making our own film, even though it may be characteristic of an «imperfect cinema in the sense of the entertainment industry’s canons of language and form», in the words of Jacobo Sucari Sucari[12].

Parity between all the community members at the technical, intellectual and cultural level to which Ruby refers may be impossible. However, to what extent is it necessary? Parity in the community must be a given but at the level of power: power to do, to reflect, to decide, to question, to imagine. Communities comprise a diversity that supposes in itself a richness that enables the sharing of knowledge and responsibilities and the generating of knowledge. Collaboration consists of that: recognizing the need to combine this knowledge, resulting from the social as well as the technical, artistic or affective fields. In this way, the notions of the expert or outsider become blurred and authorship moves to a collective conception, one which recognizes creative capacity and artistic sensitivity in all participating subjects.

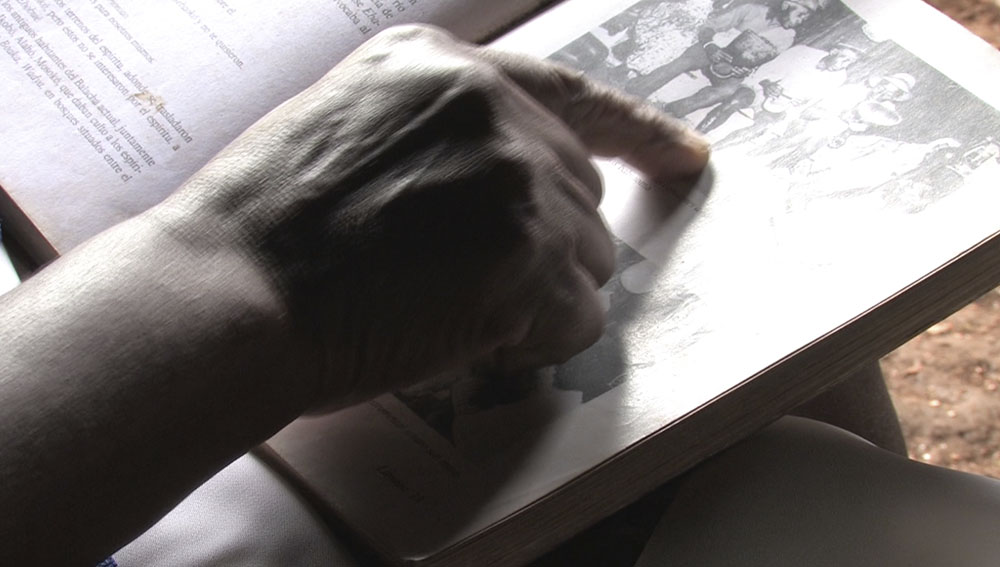

So far, the Laav_ has implemented, in addition to the aforementioned work group La Rara Troupe, three more projects[13], each linked to a community of practice. Puta Mina was proposed as an audiovisual excavation on the disappearance of mining and its associated life forms through a montage-confrontation of dialogues by women connected to mining with images made by miners in galleries that are now practically inactive. Women’s voices thereby resonate in a space that has not belonged to them but of which they have been an essential support. With Proyecto Teleclub, we opened a line to the rural world, which is affected in Spain by an intense depopulation and acculturation process. We chose as an axis for the project a teleclub, a sociocultural venue in a small locality near the city of León in which we had detected an interesting confluence of old and new inhabitants. We attempted to create a group with the aim of its working from the daily life of the space but the dismantling of the rural society itself prevented the project from reaching completion, for reasons that included the venue being controversially closed midway through the process. We are currently trying to analyse and assess the learnings that a «failed» project might have brought us in order to continue with the line of research on rurality.

The final project, Libertad, invites adolescents as well as teachers, artists and mediators to make a feature film about repression and youth during the Civil War and the Franco regime, based on the oral testimony of a woman who in her youth experienced the darkest side of our history. In this case, we suggested analogue film format (16 mm.) to be used for the audiovisual production, with handmade developing by the participants themselves. The physical and collective work with the historical and cinematographic material is taking shape —as we write— in a complex encounter over time between young people with very different socio-political environments.

All these experiences have constituted a learning space in which to propose new artistic and research paths from within the framework of the museum and audiovisual anthropology. We try not to forget, while preparing new projects, that each has to suppose a questioning of our own journey.

NOTES

This text was written as a request from Cinema por venir (Sonia Martínez and Miguel Ángel Baixauli) Issue 12, Concreta, November 2018. This is the original version.

[1] Contemporary Culture Course, MUSAC, 2017. Online at: https://vimeo.com/239484758. [Most recently consulted on 9 August 2018].

[2] Paulo Freire refers to banking education as that based on the deposit of knowledge from the educator to the educatee, ruling out any trace of bidirectionality in this relationship and, much less, any critical and transformative capacity in the educational act.

[3] Online at: http://raraweb.org. [Most recently consulted on 9 August 2018].

[4] Russell, Catherine: Experimental Ethnography: The Work of Film in the Age of Video, Duke University Press, Durham, N.C., 1999.

[5] BAIXAULI, MIGUEL ÁNGEL: «Notas sobre, para y con el LAAV_», Laav, 2017. Online at: https://laav.es/notas-sobre-para-y-con-el-laav_-miguel-angel-baixauli [Most recently consulted on 9 August 2018].

[6] MacDougall, David: Transcultural Cinema, Princeton University Press, Princeton, N. J., 1998.

[7] Russell, Catherine: Óp. cit. Bill Nichols: «The fragmented and hybrid identities produced in a multitude of “personal” films and videos have been celebrated by critics and theorists as forms of “embodied knowledge” and “politics of localization”».

[8] The chapter titled «Autoethnography: Journeys of the Shelf», always has the first person in the singular form, unlike the We assumed by the Laav_.

[9] Bergala Alain: La hipótesis del cine. Pequeño tratado sobre la transmisión del cine en la escuela y fuera de ella, Laertes, Barcelona, 2007.

[10] Agüero, Ignacio: La imagen congelada. II Seminario Punto de Vista, 2014, Gobierno de Navarra, p. 57.

[11] Jay Ruby in «Speaking For, Speaking About, Speaking With, or Speaking Alongside-An Anthropological and Documentary Dilemma», Visual Anthropology Review, Autumn 1991, Volume 7, Number 2. pp. 57-58. Ruby repeatedly uses the expression «shared authority», distinguishing between authorship and authority.

[12] Sucari, Jacobo: «Retóricas de lo participativo en el documental social», DSP Plataform, La Virreina, 2017. Online at: http://plataformadsp.org/retoricas-de-lo-participativo-en-el-documental-social [Most recently consulted on 9 August 2018].

[13] Online at: https://laav.es/category/grupos-de-trabajo [Most recently consulted on 9 August 2018].