Riot at the psychiatric hospital,

the weather man was hanged for forecasting

hail, lightning, thunder and howling wind.

The Convention of the Deranged has met

The Convention of the Deranged has decided that

tomorrow will be sunny and fine.

Kortatu

January 2019

Key words: mental health, art education, art museums, community art, self-representation, affective politics, audiovisual.

The year was 2012. The place: León, the capital of a northern Spanish province and with a population of just 130,000. Its public health system ran a psychiatric hospital on the outskirts, the Santa Isabel Mental Health Hospital, which had a small supporting network through primary and psycho-social[2] care centers. Meanwhile, the León Association of Relatives and Friends of the Mentally ill (ALFAEM) was gaining in strength on the basis of a protective discourse that drew funding for the creation of supervised flats, residences and other resources for people diagnosed with a mental disorder.

Bearing several voice recorders and small home video cameras, we began by giving presentations at the hospital and different mental health centers, teaching those who approached us the main aims that we had set for the project. These we explained as a workshop which taught how to use audiovisual media in order to narrate our own life experiences in the first person.

We started the workshops at Santa Isabel Hospital and within a few weeks we realised that we were running a characteristic risk with this type of approach for a museum that attempted to work with people and in the context of reality: we were being used as an occupational resource by the hospital or by those who approached us, who often had no interest in the audiovisual format and who showed an unwillingness to speak from the first person. The approach included radio programs with guests, dedicated songs or discussions with medical teams and other healthcare professionals, despite our efforts to broadcast something different that went beyond customary radio formulas.

In a few months, we decided to leave the hospital and started to work in a stable, continuous manner at the museum. We regarded this as a neutral[3] space for those from the hospital or ALFAEM centers. It was “a space without a diagnosis”, as one colleague said afterwards (Sola, 2015, p.234, paragraph 5). The museum therefore became a space that convened from the “normality” of an artistic workshop, for which diverse people “enroll”: local artists, students, those known through their other activities at the museum, and others who learned of the workshop from the experiences of users from the hospital or the ALFAEM or even the medical teams themselves.

It was then that the project took its first unexpected turn; the desire arose in us to remain together, to continue with the workshop but considering what we “could do” and therefore what we as diverse people “could be” if we continued to meet and work collectively. This gave rise to the group of people who would become the driving force of La rara troupe. It stemmed from the desire to share a space of truce and to break with our daily diagnoses, marking out paths that are not only connected with mental illness but also with the social dissatisfaction that brought us together.

We named the workshop Yo/nosotrxs (I/We) to express not only the illustrative but also the communicative purpose of the act of making audiovisuals. But beyond projective proclamations, the bodies that came together were able to generate the confidence that we belonged to something that was still to be done and especially something that was to be done by us. This was perhaps the feeling that encouraged us and surrounded us at meetings and that ran cross-sectionally through all the workshop’s actions in this second year.

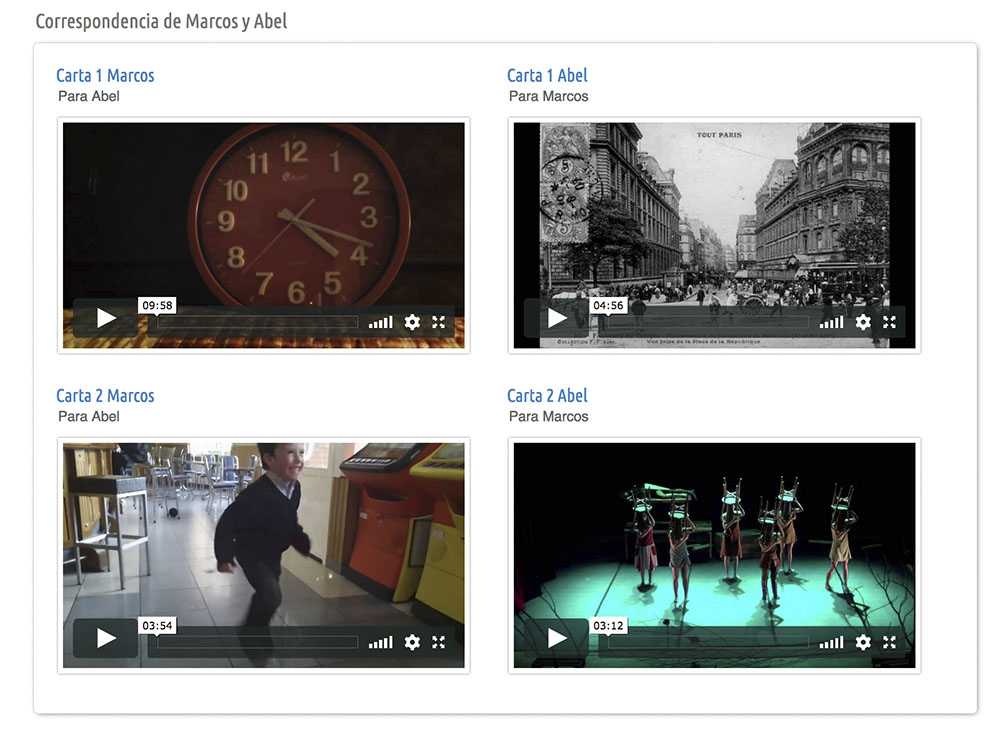

In this first stage, the methodological approach was the exchange of video-letters, first between us and later with other groups outside León. These exercises achieved their purpose; they returned a state of equality to the different voices that had been stripped of all authority for being small, invisible or confused. We became aware of the minimal differences that existed in our desires and fears, opening ourselves up to the modesty of feeling bad, knowing that this is what happens to you as a consequence of the feelings and reflections that come out from the images, as a result of the depth that a silence or the histrionics of a laugh might possess.

Yo/nosotrxs became a space made possible by the coexistence of those who otherwise could not coincide in the same space. We had won a battle: the right to be together, to create a “community of alienated bodies[4]”. However, this was not enough for us; we also needed to obtain the means to create, investigate and produce knowledge from our encounters and do so in our own way. Listening to another person and recognizing him or her, this was to be the first step to coming together, renouncing inclusivist correction because, according to Aracil (2016): “the reason or idea of inclusion plays the leading role in most clinics and therapies for the mentally ill. It is as a victimizing practice which aims to neutralize the know-how of the other”. At our meetings, the fact that we were together involved deactivating victimized individualities through the enhancement of the vulnerable, anomalous, sick or rare, opening up a space for the knowledge of the bodies who suffer and starting to work from a common starting point; expertizing life, politicizing discomfort, inscribing it in the accumulation of disregard for contemporary ways of life.

In 2014, the workshops were extended and the activity exceeded the working day in the museum. We met to record, enjoy a coffee, chat about the weekly meetings, the difficulties we encountered with certain colleagues or the ideas that occupied us. We proposed texts to read together and guests whom we would like to welcome[5]; we started to feel that the diversity that we embodied was covered by the skin of a shared drum and we started to breathe and generate residues while we experimented with our own limits and desires. The resonances were multiple but we needed to narrate them collectively.

At this time, we decided to call ourselves Rara web (Strange Web). The aim was to highlight the meeting space with “les otres”, a virtual window from where we were showing ourselves a world that did not see us but that named and diagnosed us; a new frontier had just been crossed. We were no longer “me and the world”, “me and the outside”, we managed to be plural from the identification of our limits and corporalities.

As Garcés (2011) states, dealing honestly with reality would be, not so much “adding the victims’ vision to the image of the world, but altering our way of looking at it in a deep-rooted way”. Rara web attained that transformed gaze exactly, right from when it was proclaimed in the plural. Moreover, as I said above, I would like to stress the idea that in Rara there are no more “victims”, people who have approached the group at first by “belonging” to a diagnosis have managed to escape[6]; a space with a host of possibilities has been opened from the desire to be others or even better, to be ourselves.

A new change affected the project, in which Rara web became the group now known as La rara troupe. La rara stopped representing (seeing themselves as) individualities and began to act as a collective body, making their films using everyone’s ideas, implementing affective policies more than ever and putting emotions into play and knowing how to make them circulate creatively (Ahmed, 2015).

Mental suffering is what brings us together and causes intensities that transcend individual limits; it is in pain and discomfort where we anchor the sense of being together and it is from pain and frustration that we feel authorized to produce ways of naming ourselves and addressing ourselves.

On the other hand, this relationship of affections is organized in a circular manner. It appeals not only to identities, which are organized collectively and not hierarchized by professionals or medical diagnoses but to the filmic productions that we make. This is interesting because it affords a relevant place to the audiovisual not only as transmitting tools[7] but as objects that work affectively within the group, becoming links in the affective identification that we establish with them. Returning to Ahmed, it is perhaps enlightening how “in affective economies, feelings do not reside in subjects or in objects but are produced as the effects of circulation” (2015, p.31). This is exactly what happens in La rara, which produces or creates movement around the relational effects (of an emotive type) based on a circular organization between the subjects and the objects that we produce and with which we identify.

We started 2015 with a creative residence as the guests of Azala[8]. This was a week-long experience of coexistence that enabled us to test how far we could pressurize the spaces of collaboration between us. This was a new scenario where private space and common spaces, creative work and each person’s specific moods had to find their place. It was at this time that we began to be called La rara troupe, a name that we intend to keep and that arose from the idea of travel offered by the residence.

The project proposed investigating the idea of troupe as a collective of artists or creators who move together, as a “company” in the original etymological sense of the word, as a body of actors, dancers or technicians etc., as well as the roles each of us play in the collective in order to recognize ourselves in them or to question them. Moreover, we were moving from our reference “institutions” on a daily basis; from our work, from the hospital, shared homes or the museum, so we decided to name the residence des-plazados (dis-placed). In short, the working week together was an opportunity to delve into the notion of the community and the contradictions and frictions that occur in our collaborative work.

We undertook many audio-visual exercises that week, starting with individual presentations and continuing with group exercises. My presentation exposed a concern that had occupied me for some time; my role as “the uncoordinated coordinator” and this is how I expressed it:

Perhaps what Azala taught us as a group were more the differences between us than the similarities; those who wanted to experiment with the camera compared to those who were enjoying the best days of their final years; the liters of coffee and the kilograms of sugar we consumed seemed to ratify the exercise of freedom that many colleagues said they needed.

The days of residence passed with an intensity that our guest/reporter Martín Correa (Sola, 2015, p.297) described:

(…) La rara is encountering the questions, detecting the collective and individual needs and this is a giant step. In the face of a creative approach, the “what to do” is not only relative to a format or a tool (the “how”). The “what to do” is subject to a need or desire, to a search that is sometimes difficult to detect because we come from a life path marked by an excess of control, where one is almost always told what to do. I said then that I have seen that they have created that context of rest, space of fracture, habitable limit, in relation to the former conditions of oppression: and the needs are becoming visible, those that were there before, but that are now becoming visible, communicating, expressing themselves. It is there, with these first seeds it is necessary to get down to work, compose, create. And that is what perhaps needs to be developed. Many creative processes are focused on the tool, La rara troupe already knows that the tool is both a means and an end for telling something that hurts, something that in many ways “is urgent”, which is like a “scream” from within. La rara troupe has found or has begun to find that “cry” that “is urgent”. Now it is time to continue analyzing formats, tools, ways of telling and building a body for what is tellable. (…)

Building un cuerpo para lo contable (a body for the tellable) was the yearning contained in the two videos that we projected at the end of our residence:

The first video created with the camera a choreography of bodies that were under the sign of the hug, as a metaphor for the communion between us. Picnic, on the other hand, was an exercise where the camera was only a guest to the scene of conflict that occurs in a totally unpredictable way.

I would like to think of the first as a video-machine in the sense that the audiovisual tool organizes and puts bodies to work in order to exercise the metaphor of collective work. The second acts as a video-symptom, where the discomfort produced is largely a consequence of not knowing how to shake off our mental states and individual obsessions. In any case, and based on listening to the assessment interviews we conducted, the week in Azala signified for La rara troupe an experience of life and freedom that was unfailingly linked to the creative act.

Personally, I enjoyed listening to a phrase that I said back then in this recording: “I have learned how to accept myself in the group from my professional role” [9]. I think this refers to the experience of shifting position, learning to be someone else, knowing how to incorporate learning slowly although this forces you to question yourself and observe yourself in an often obsessive and frustrating manner. Doubting yourself as an exercise to account for yourself, these are two ways of shifting in one’s work that cause pain and fatigue but that I understand as necessary conditions in creative projects where the body is present.

La rara troupe, from that moment, was so named as a group of artistic creation, but it has never renounced its political identity as a think-tank on mental health through the investigation of two issues:

– The generation of contemporary ways of life that make us ill and produce multiple discomforts and that, ultimately, also make us incapable of organizing ourselves collectively.

– The use of vulnerable or precarious lives as part of a normalizing and capacitating discourse that seeks to open up spaces where voices that are said to be ill can be integrated.

This is an odd time enabled us to connect to our daily existence in April 2016. Recording moments discovered at random or explicitly sought, we used our cameras to share time spaces loaded with everyday life. The film expressed the dignity of our vulnerable lives and was intended to show the importance denied by small things, endowing them with interest, which is also a metaphor for our small and precarious but significant and valuable lives.

Son curiosos estos días (2016)

A new change occurred at this time, one that was not so much endogenous or self-referential but exogenous or reflexive. This was the ability of the project to imagine a larger space within the museum for research and implementation of creative projects with communities. Since 2016, La rara troupe has been integrated into the Laav_ Laboratory of Experimental Audiovisual Anthropology[10], which was launched in the Educational Department of MUSAC and became the test-tube project from which to learn from the group’s constant experimentation.

In 2017, invited by Alfredo Aracil, we formed part of the exhibition Notes for a Destructive Psychiatry. Here, we proposed an audiovisual exchange with another group from Madrid that was coordinated by the mediation team of La Sala de Arte Joven, the venue for the exhibition. Therefore, two videos were born out of the aim to investigate the construction of a collective body, managing ideas that crossed between performance, rite, fiesta and play.

The first video represents an experience arising from the reading of excerpts from the book Ser o no ser (un cuerpo) (To be or not to be (a body)) by Santiago Alba Rico. We were able, not without great effort, to reach consensus, to assemble in a half-abandoned square of one of those half-finished neighborhoods that exist in any provincial capital and make a paella. The video could be divided into two sections; in the first (until minute 4’45”), we collected images taken on the day we explored the square and in the second, we filmed while we were cooking the paella: in both cases we used the sound from experimentation exercises that we recorded in the space.

The Madrid group responded with a highly dynamic video in which play was highlighted as a collective experience, so we decided to conclude the co-relation by recording a party to provide continuity while enabling us to include a variety of different actions. As a cinematographic reference, we used Tongues untied (Riggs, 1990). This inspired the concluding choreography, subtitled with the text of a colleague, Ángela María, who gave the video its name. The rest was an odd recording of the proposals made by each of us, from a karaoke to a free painting workshop that also involved reading or dressing up.

Apuntes para una psiquiatría destructiva (2017)

Apart from these videos, the participation of La rara troupe has signified recognition from legitimate cultural spaces. La rara definitively abandoned its links to the training workshop and began to be a creative space again. This does not come from La rara but rather from the space of artistic legitimation par excellence: the exhibition.

Between the fall of 2017 and the spring of 2018 we experienced some hard times. Some people quit the group permanently and those who remained strived to balance the need for activist demands on the part of many colleagues with the radicalization of the artistic proposal of others. Our latest film, La Humana Perfecta (The Perfect Human), yet to be released, coexists in a few weeks with texts by Félix Guattari and the film Le moindre geste by Fernand Deligny in the context of a reading group and a thought program[11] at the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid. Beyond the symbolism of an anonymous group defined as “rara” sharing a table with recognized and authorized names from the world of culture, La rara troupe was convened to show itself as a space with accumulated wisdom sufficient to produce and share knowledge. We arrived at this using our own (self) tools created or what is the same, epistemologies located in our discomforts.

With this brief tour of the work of La rara troupe I have wished to highlight two things: firstly, the museum’s current role as a privileged place for social research from artistic research methodologies; and secondly, the need to enable spaces for organization in community with subalternized or minorized identities and doing so from the conscious taking of the word and images, the construction of our stories and the creation therefore of our own genealogical narratives.

The School for the Deranged, which is La rara troupe, makes demands and brings into play its life, its emotional states and its discomforts and becomes conscious of a shared alienation. This unites us in a journey where neither medical diagnoses nor neoliberal recipes of social adjustments and pills make people fuller or happier.

I needed six years of Rara to give up on my desire to burn down the museum. Now, I just want to fill it with those who are deranged; it gives back meaning to my work here.

NOTES

The first version of this article was originally published in Re-visiones in December 2018. It is a first person narration of the project “la rara troupe” (The Strange Troupe), a space for creation and co-existence between a group of people both with and without a mental illness diagnosis. This space has been conceived and shaped since 2012 in the Educational Department of MUSAC (Castile and León Contemporary Art Museum). We recommend both reading the texts and watching the videos linked in the text.

[1] Chus Domínguez, audiovisual artist. chusdominguez.com

[2] The public Mental Health System has shifted radically from the Francoist asylum or mental hospital to the current semi-private welfare state that was introduced in the 80s.

[3] This does not mean that we think that the museum as an institution is neutral, rather the opposite. As Preciado (2017) says, the museum is a machine that produces subjectivity and reproduction of regulatory codes.

[4] See video “El cuerpo del delito/The Evidence” in this paper. Minute 4’45.

[5] Another symptom of our forming a research group was the desire that arose in the group about (self) training. This led us to begin to expand our audiovisual meetings by adding texts and guest voices. We started in February 2014 with the Grupo Esquizo Barcelona and since then workshops, talks and meetings, as well as several readings suggested by us, proved key to the growth of La rara troupe. For an exhaustive tour of guests and texts, see raraweb.org/blog

[6] I only provide observations that are directly drawn from the La rara troupe workspace and relationship as I am unable to extend them to other contexts.

[7] The audiovisuals we produce are not intended to be tools of self-expression or an anti-stigma pamphlet but are creations of our own imaginations and, as such, of our subjectivities in the making.

[8] Creation space located in Lasierra, Álava. www.azala.es

[9] https://archive.org/details/2.EntrevistaIdaAzala/3.entrevistas_vuelta_Azala.mp3, min. 38

[10] www.laav.es

[11] http://www.museoreinasofia.es/actividades/fuerza-posible-hacia-poietica-vivir-juntas

REFERENCES

Aracil, A.(2016). “Saber-hacer con el otro, La Rara Troupe o la potencia de la anomalía”. En: https://laav.es/saber-hacer-con-el-otro-la-rara-troupe-o-la-potencia-de-la-anomalia-alfredo-aracil/ (Recuperado el 10/06/2018)

Aracil, A. (2017). Apuntes para una psiquiatría destructiva. Catálogo. Madrid.

Ahmed. S. (2015). La política cultural de las emociones. UNAM (ed.). México, D.F.

Garcés. M. (2011) “La honestidad con lo real”. En Álvaro de los Ángeles (ed.), El arte en cuestión. Sala Parpalló, Valencia.

Preciado, P. (2017) “Salir de las vitrinas: del museo al parlamento de los cuerpos”. Vídeo de la conferencia en https://vimeo.com/239484758 (recuperado el 10/06/2018)

Riggs, M. (1989) Tongues Untied. Película documental. 55’. EEUU.

Sola, B. (2015). Prácticas artísticas colaborativas, nuevos formatos entre las pedagogías críticas y el arte de acción: La rara troupe. Tesis Doctoral. ULE.