January 2018

“When the Baal Schem had a difficult task before him he would go to a certain place in the woods, light a fire and recite a prayer. And in this way the task was completed.

When a generation later, his son was faced with the same task, he said: ‘We can no longer light a fire, but we can pray’. And everything happened according to his will.

When the time came for the son of his son to resolve the same task, he said: “We can no longer light a fire, nor do we remember the prayers, but we know the place in the woods, and that is sufficient.” And sufficient it was.

When finally the son of the son of the son was called upon to perform the task, he sat down in his golden chair, in his castle, and said: ‘We cannot light the fire, we cannot recite the prayers, we do not know the place, but we can tell the story of all this’. And, once again this had the same effect as the actions of his forefathers”.

Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism. Gershom G Scholem. Translation based on the original compiled by Scholem and Jean-Luc Godard’s adaptation at the beginning of his film Hélas pour moi.

In the Sixties, at the highpoint of the decolonisation process, the accusations that identified anthropology as a necessary collaborator of colonial expansion and questioned it’s validity as an academic discipline intensified. These critical voices, that frequently came from within anthropology, were directed, amongst other things at the tendency in ethnographic monographs to situate the societies being studied in a kind of unchanging limbo outside of time. In short that this was a rhetorical device that refused the possibility of change and at the same time neutralised the importance of the devastating effects of colonialism.

This was a critical thinking that attacked the heart of the discipline and had something in common with those who questioned the idealistic intentions of the “fly on the wall” documentary technique in it’s attempts to register reality. Both positions seemed to ignore the limitations of the observer, whose point of view is always conditioned by their subjectivity (and technical skill) as well as the explicit and implicit relationships of power established between the subject and the object.

How then to interpret history? Certainly interpreting (or making) images, a dialogue or a situation recorded in the present that references historical events, suggests the possibility of new perspectives. Points of view and proposals that demand aesthetic forms capable of approaching the historical -in truth, the past- in audiovisual works that are unquestionably a register of the here and now.

You could say that working with archival images escapes these limitations. But all historical archives are by definition incomplete, and audiovisual archives even more so as they are limited to the relatively recent past and were only created by the very few with access to the economic resources and technical expertise to make recordings. And even then archive images are by no means an inmutable storehouse of the past of and by themselves, they also demand, or require, a historical activation in the present.

In fact we came back to something cinema has always longed for: to film the past with all that this task implies of both the magical and the intangible. A variety of procedures that might begin with the earliest historical reconstructions of the silent newsreels and take us to the work of John Gianvito in Profit Motive and the Whispering Wind. This film tells the story of the violent past of the United States through the traces and inscriptions left on commemorative monuments, and I could also mention Claude Lanzmann or Eduardo Coutinho with their use of oral history, the word and the testimony of the witness.

The Jewish story that introduces this article is inspiring in the sense that, metaphorically, it could be understood as referring to distinct audiovisual strategies that at different times address a historical or mythical event that was never recorded and yet obstinately continues to influence the present. It’s a text I regularly come back to when confronted with my current project that attempts, in the present, to approach the maleable and elusive layers of a history that sometimes overlap, sometimes contradict and frequently dissolve in recounting and interpreting past events.

The episode I am concerned with is the death of Sas Ebuera, the last leader of the Bubi people who resisted the Spanish colonial occupation of Fernando Poo (actually Bioko). In 1903 Sas Ebuera died in captivity after being taken from his home by mercenaries working for the Civil Guard. According to the authors Dolores García Cantús or José Fernando Siale this incident triggered a series of violent conflicts between the local resistance and the Spanish authorities that, in the end, decimated the Bubi population.

There are no photographs or portraits of Sas Ebuera. Only a handful of documents, often contradictory, prepared by the colonial civil service. Texts written by and for the colonial administration in which the veracity of that which is recounted is absolutely irrelevant. They are physical, legible and palpable documents that can be filmed. They are also partial, biased and open to interpretation. The next question that emerges is logical: What about the versions of this event that circulate amongst the Bubis?

Aware that I am arriving more than 110 years late I cross the south of the island looking for people who can tell me what happened between the 26th and the 30th of June 1903. The stories aren’t clear either: there are doubts, contradictions, things forgotten and erroneous data. There is even a woman who claims to have reliable information -with the unquestionable authority of the written word- that sends me back to one of the most popular Spanish versions, an extract from a monograph about the Bubi people.

I am left with the option of returning to the “neck of the woods”. In this case literally (Photo 1). But no luck here either. You can more or less get to the place, but the village where Sas Ebuera lived and was arrested disappeared a long time ago -probably as a result of the policy, imposed from the capital, of grouping small villages together- Where should I place the tripod? In which direction frame the image? What size should it be?

Foto 1

I go back to the oral histories but from another perspective. In the end it isn’t about making a forensic reconstruction of events. Barthes writes: “The closer a document is to a voice the less distanced it is from the warmth that produced it and the greater are the grounds of it’s historical credibility. This is why the oral document is superior to the written document. And the legend to texts“.

Even though none of the Bubi stories agree on the precise details of Sas Ebuera’s death many of them do agree about a curious epilogue: the body of Sas was buried next to a natural spring on the outskirts of Santa Isabel (now Malabo). “It is said that”, contrary to common sense, the spring flows during the dry season and runs dry during the wet season.

I found the spring. It is a physical place, unarguable, that I would have passed by without noticing if it hadn’t been for the “marker” that activated it historically in front of me and my camera (Photo 2). It could be described as “secret”, it is a place of mourning. This is the first real place that is unequivocally historically significant. And yet it’s attraction derives from a legend rather than facts and irrefutable documents. From a story that tells of a phantasmal presence that apparently reveals itself through a seasonal peculiarity.

Foto 2

But it’s not about thinking of the commemorative potential of the place. Referring to places of conflict, Louise Purbrick writes that this operation implies “underestimating the way in which the past is continuously inserted into the present. Places of conflict become powerful representations in their own materiality. They contain the footprints of the dead and show signs of violence. They are contaminated in the anthropological sense of the word“.

Invoking these kinds of places obliges us to enter the unsettling liminal world of ghosts. “A kind of residual insistence, almost material, that interrupts and resists all attempts at negation. This is a ghost, after all: something that has gone, something dead, but that refuses absence: something neither here nor now, but that continues to stain and contaminate the here and now“, as understood by Steve Shaviro, returning again to the idea of pollution. The ghosts resist negation, being sacrificed to the pure historical narrative or deactivated in the simple interaction of facts and dates.

At this point, whilst going over recent recordings, I realise that I didn’t record direct sound and that I need to return to the spring. The silent image is lacking depth, an inseparable part of its “materiality” and, paradoxically, my instinct tells me that to recover this recording in the most literal way -that is mostly the sounds of traffic and street vendors- I get closer to this spectral territory.

In their installation Spirits Still Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Veréna Paravel isolate 686 frames from amongst the 130,000 that constitute the raw material they worked on in the film Leviathan. These images correspond to ghostly apparitions, invisible when played back at normal speed. The capricious play of the sky and the sea, light and shadows that draw faces; vulnerable, fleeting presences that might suggest the bodies of those lost at sea.

Neither their work (I believe) nor my own are talking literally of paranormal phenomena, ghosts don’t manipulate zeros and ones to appear by chance in digital images and sounds registered in Malabo are not psychic sounds. Rather the material properties of audiovisual media, specifically anthropological documentation, activate perceptual responses that allow us to recover fragments of the past -history and inevitably the presence of the dead- in a lived, palpable, thoughtful and moving way.

To summarise, it is oral history, the legend freed of the pretence of factual historical reconstruction, that becomes, finally, my starting point. That allows me to build a model in which the traumatic past is activated through the spectral qualities of visual and acoustic registers that maintain their power even in the digital era.

And it is thanks to this shift in perspective or attitude towards oral history -to continue the Jewish legend we started with: that the history being told produces the same effect as the fire, the prayer or the place- that we can open up our work to other narratives and footnotes. Material that is, in the end, vital in helping us to understand the extent of the impact of decades of colonialism, even now, on those societies that have been subjected to it.

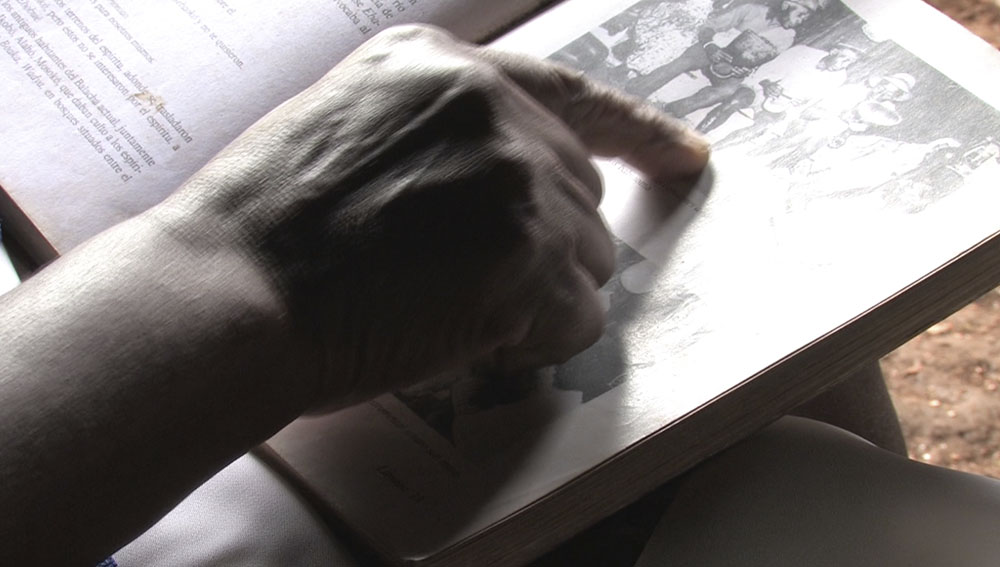

I go over the testimony of the woman mentioned earlier. After browsing through the first pages of the monograph on the Bubis and the text on Sas Ebuera based on Spanish sources the woman continues to turn the pages. She stops at one that has a photograph, the footnote indicates only “a fortune-teller”. The woman points to the photo, pronounces the name of the subject photographed and explains the distant family ties that link her to him, “he died a long time ago”, she signals (Photo 3).

Foto 3

That which in anthropology is a category, cold and interchangeable, in her voice becomes an individual, a name and a unique, untransferable existence. An individual, even if no longer living. A personal history fleetingly elicited that challenges the historical model associated with official, allegedly scientific, documents. This act that provokes, momentarily, a distinctive perspective, almost ghostly, of a past ripped apart by years of colonial administration.

In Vita Nova Vincent Meessen investigates a similar situation. The Belgian artist begins with an image from 1955 in Paris Match that Barthes analysed in his Mythologies. A close-up of an African child soldier in the French army. In Ivory Coast he finds the young cadet, now elderly, and shows him a copy of the magazine. “This is your grandfather”, he tells the grandchildren who surround him. The image is no longer an act of propaganda but becomes a personal document, the history of an individual that emerges from the past to mock the imperial colonial project.

In conclusion, in these lines I have tried to describe, through my personal creative considerations, a few elements that are crucial for my work. And also I suspect necessary for a debate about contemporary visual anthropology: the almost unlimited richness of oral testimony with its words, silences, gestures (and the diversity of perspectives from which we can listen to this testimony). The individual and collective histories that radiate from the places of conflict and the material quality of the audiovisual medium with its paradoxical capacity to recover the disappeared and the extinct through the exploration of its own limits.

Javier Fernández Vázquez is a film director, audiovisual producer and founding member of Los Hijos, a collective dedicated to non-fiction, video art and experimental ethnography. Among his works are the feature films Los materiales (2010) or Árboles (2013) and the short film January 2012 or the apotheosis of Isabel la Católica, which won several prizes at international festivals (Punto de Vista, FidMarseille) and have been projected in numerous centers of contemporary art and formed part of collective artistic exhibitions. His complete filmography has been the subject of several retrospectives (Lima Independiente, Distrital, 3XDOC). Javier works as an associate professor in the Department of Audiovisual Communication of the Carlos III University (UC3M) and belongs to the research group Larga exposition, the narrations of contemporary Spanish art for the “great publics” of the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM). Previously, he has taught visual anthropology at UNED and experimental film at Escuela SUR. He has also contributed to the programming of audiovisual cycles in CA2M and in Tabakalera Donostia.