March 2019

Whatever is unnamed, undepicted in images, whatever is omitted from biography, censored in collections of letters, whatever is misnamed as something else, made difficult-to-come-by, whatever is buried in the memory by the collapse of meaning under an inadequate or lying language – this will become, not merely unspoken, but unspeakable.

Adrienne Rich, On Lies, Secrets, and Silence: Selected Prose, 1966-1978.

Summer 2014, Madrid. It’s very hot and I feel my quadriceps turning increasingly numb. We’ve spent four hours jumping on the same axis to the almost ecstatic beat of hard techno. Half of the girls around us have already removed their shirts and some even their bras. No one looks at them, at least not without their consent. They dance alone and in groups, they sweat. Sometimes, with their eyes shut, they burn up the floor. It’s the first time I’ve experienced something like this.

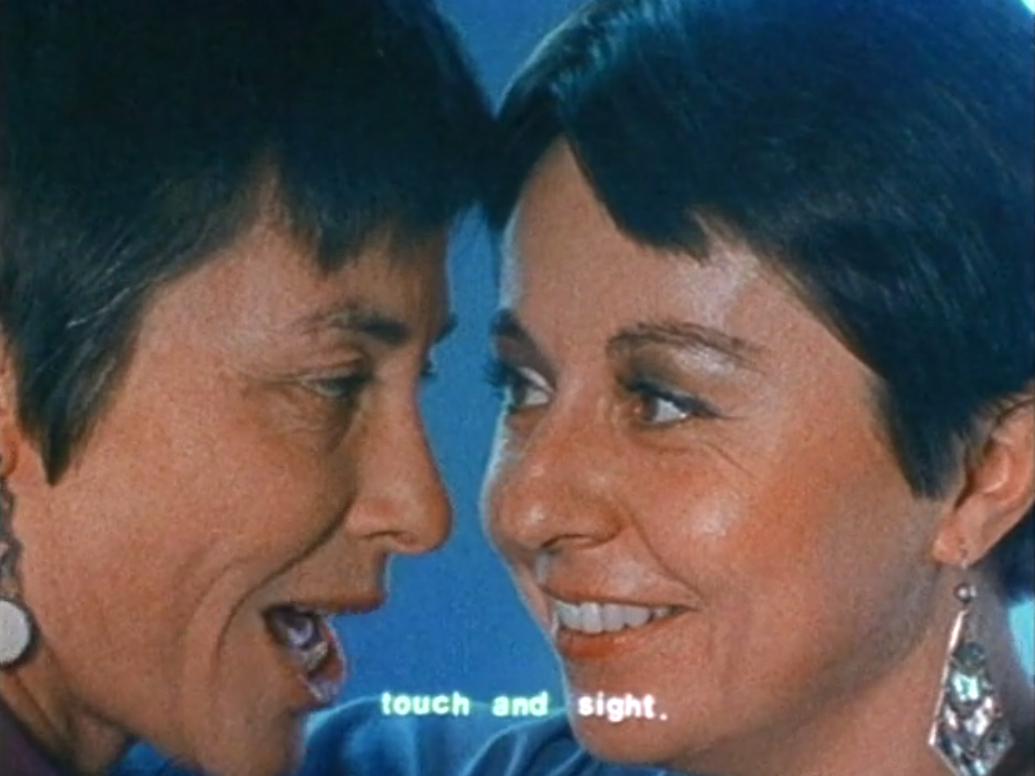

Summer 1973, Los Angeles. The metallic sound of techno softens and becomes more organic, clapping stirs up the drums and the ritual begins. The women, now in black and white, hug and sway gently, some, many, raise their arms and tighten their fists. A voice-over says: “This film is made for women, by women, and it’s dedicated to women.” It’s the first time that our bodies have been filmed out of love, desire and respect. Behind the camera is Aggressa, the pseudonym that Barbara Hammer (USA: 1939-2019), a pioneer of lesbian cinema, used in her early works.

The films that Hammer made over more than fifty years constitute a valuable archive and repertoire [1] of experiences, places and identities traversed by that “other” desire, the one that is non-hetero-regulated. Her very first shots of women’s bodies fucking, of her own body, of her lovers and girlfriends, as well as of the places they inhabit and re-appropriate, construct an iconography that is hers and one of the first positive representations of the sex-affective relationships between women. But, above all, there is archaeology in her work; it digs for references, yearning to fill the gaps that history has left empty or has erased violently. It is in this context that the performative becomes urgent and the body before the camera reveals what has been erased by acting as a vehicle of past, present and future experiences.

These historical voids and forced disappearances of dissident imaginaries and feelings have led to an audiovisual anthropology founded, in addition to the performative, on a collage or mash-up of interviews, footage encountered and all those documents that have potential to be filmed (letters, books, photos, maps). It involves, therefore, disjointed, fragmented and non-linear historical reconstructions, narratives traversed by a time other than that of neoliberal capitalism and models of sociability and Western hetero-regulatory culture. LGBT ethnographies imply, therefore, a new time, composed from and through the body and its agency.

Following on from the autobiographical and activist progression initiated by Hammer and other experimental filmmakers like Su Friedrich (USA: 1954) during the 1970s and 80s, the nineties brought an international explosion of sexually dissident anthropological cinema. This inherited from its pioneers the inscribing of the self and deeply feminist narrative enunciation, as well as the hybridisation of genres and materials, together with meta-reflection about the cinematographic medium and its hegemonic systems of representation. The incursion of the internet into the domestic sphere and the onset of the cyberfeminist movement (in 1991, the Australian collective VNS Matrix published A Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century, and in 1997 the First Cyberfeminist International was held at Documenta X in Kassel); the democratisation of image production technologies from the commercialisation of the first digital video systems; the global HIV crisis; and the beginnings of the queer movement; these are some of the new materials and trends that traverse the artistic practice of this era’s filmmakers.

Sometimes you have to create your own history. The Watermelon Woman is fiction.

Cheryl Dunye, Watermelon Woman: 1996

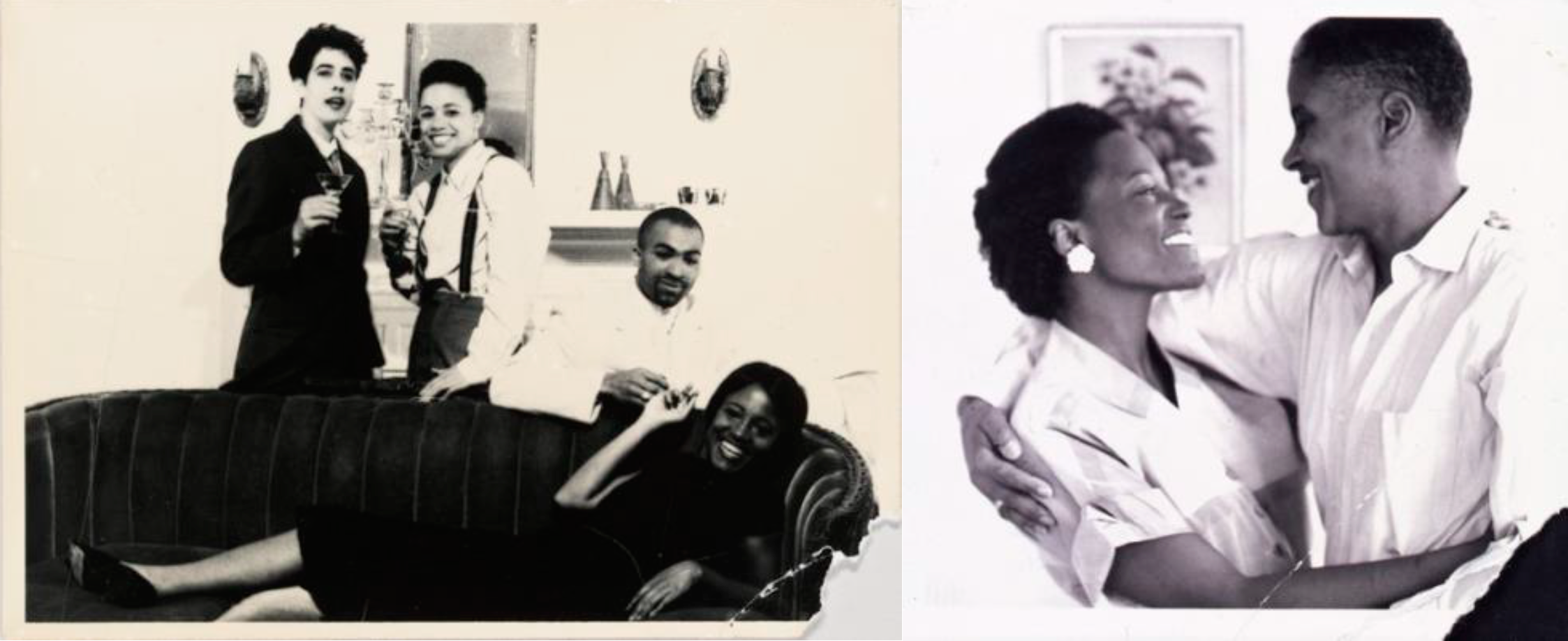

In her first feature film, “The Watermelon Woman”, made while she was still completing her university studies, Cheryl Dunye (Liberia: 1966) used generative fiction as a tool for historical rewriting. Dunye created the character of Fae Richards as a retrospective alter ego by which she explained herself and generated, as an African-American lesbian, a positive genealogy on which to cling. Richards, as well as an actress, was a jazz singer and filmmaker, but her name did not even feature in the credits of classic films in which she played the “mammy” stereotype (a kind, illiterate black maid). Richards was depicted as one of those holes in history that have left us short of references or of which we only have a body that is loaded with negative representations. Parallel to the search for her identity, Dunye, in a collaboration with the artist Zoe Leonard, created a huge archive of images, documents and sounds related to Richards’s life that are too much even for the film. This is “The Fae Richards Photo Archive”, a book that compiles photographs in which we witness remnants of the personal life of Richards, an empowered woman who broke with the social norms of her time. From images, film stills, advertising photographs and small fragments of text, Dunye and Leonard invite us to speculate on her life, to project ourselves into it and to challenge the discourses of race, gender and class on which official history is built.

In addition to Leonard, during the filming of “The Watermelon Woman”, Cheryl Dunye enjoyed the assistance and collaboration of several of the age’s feminist cultural agents such as Cheryl Clark (Afro-American lesbian poet and activist), Toshi Reagon (lesbian African-American singer), Brian Freeman (performer in the group Pomo Afro Homos) or Sarah Schulman (writer and lesbian activist in the groups ACT UP and Lesbian Avengers). Working in a community or collective has been another common feature in sexually dissident audiovisual anthropology since its inception. We return to Barbara Hammer and her multiple collaborations with feminist theorists such as Kate Millet, girlfriends and lovers such as Max Almy (a multimedia artist and cultural critic) or her wife during the last thirty years of her life, Florrie Burke (a human rights defender specialising in the fight against people trafficking).

Working in a group and sharing creative processes is presented as another strategy for fighting against a system, in this case that of the film industry. Historically, it has considered films made by women, racialised people and/or sexual dissidents as minor, and even more so if their narrative and structure strays from the classical canon and the scarcity of resources and poor material conditions during its production exclude it from the quality standards of Cinema with a capital C. Through collective film practice, LGBT filmmakers seek to expand our support network and safe spaces, to share and redeem references, as well as to build our own iconographies from mechanisms such as the re-appropriation and destruction of stereotypes.

Collaborators since 1989, Shawna Dempsey and Lorri Millan (Canada: 1963 and 1965) are filmmakers and performers who appropriate elements of popular culture to generate, through irony and an extremely sharp discourse, a dyke imaginary that highlights heterosexism and mainstream misogyny. Among the icons that they take apart in their Archetype Performances are Medusa and the Little Mermaid. Dempsey and Millan subvert them and rewrite their myths and stories from a contemporary feminist perspective.

All their performances are documented audiovisually, generating independent pieces strongly contaminated by narratives characteristic of advertising, video clips, karaoke, monologues and even traditional ethnographic documentaries. This is the case in their projects “What Does a Lesbian Look Like?” (produced by Much Music, the Canadian television channel specialising in music videos, and broadcast several times on national television between 1994 and 1995) and “Lesbian National Parks and Services: A Force of Nature”, a kind of counter-nature documentary [2] in which, performing the role of the ranger and guided by a male voice-over that describes each of their movements in detail, Dempsey and Millan introduce a dyke presence into spaces where the concepts of history and biology exclude all those bodies that cannot be assimilated by the hetero-regulatory cultural and scientific system. These bodies challenge a roMANticised and subjugatory view of nature and dissident identities. To accompany their performances and videos, the lesbian rangers have launched several publications with the aim of recruiting young colleagues, such as “Lesbian National Park and Services Field Guide to North America: Flora, Fauna & Survival Skills” and “Handbook of the Junior Lesbian Ranger”.

There is a lot of posing in Dempsey and Millan’s work, understanding posing as a threat [3], that is, as a repertoire of apprehended gestures that consolidate and dismantle from an awareness of their socially and historically constructed nature. Posing and drag as lesbianising weapons, queerifiers of space, staging and identities. This is narrative cross-dressing with echoes in contemporary works like the teenage diaries of Sadie Benning (USA: 1973). Shot with a PixelVision, a toy camera that was launched by the Fisher-Price company in 1987, Benning’s videos draw from fanzine culture and the Riot grrrl movement (we recall that she was one of the founders of the legendary band Le Tigre). Benning often places herself in front of the camera in a defiant manner. As if she were a mirror, she tries out different poses, many of them loaded with pop symbolism and cinematographic references. Given the lack of characters and images produced by the media with which to empathise, Benning generates her own imaginary from the deconstruction of gender and perversion of the iconography of the star system.

A decade before Benning shot her diaries, media activist DeeDee Halleck (USA: 1940) founded New York Paper Tiger TV (1981) and Deep Dish TV (1986), which were among the first collectives and community networks on American public access television. Currently active, their main aim is audiovisual literacy and challenging the corporatism of the hegemonic media. Their programmes deal with social issues that are not properly represented in the media, mainly related to gender, race, sex, class, civil rights and ecology issues. Among the videos produced in the nineties, we find monographs on homosexuality in Native American peoples (“2 Spirits: Native Lesbian and Gay Men”, Osa Hidalgo de la Riva, 1992); reports on US public health coverage from a lesbian perspective (“Lesbian Health News”, Dyke TV, 1994); or the documentary “Homecoming Queens”, made in 1999 by the young residents of the LGTBIQ shelter Green Chimneys Gramercy Residence. I wonder what would have happened to Benning’s diaries had she grown up in New York instead of Milwaukee and had access to these programmes.

The two platforms served in their beginnings as an artistic-theoretical bridge between the United States and Europe. In 1987, Nathalie Magnan (Paris: 1956-2016), a cyberfeminist pioneer, filmmaker and activist, shot for Paper Tiger TV Donna Haraway (USA: 1944) reading or, rather, deconstructing an article about primates published in National Geographic. It was a real lesson in feminist anthropology. On her return to France, Magnan shared her American experience with her students in her classes, various publications, films and events. Now in the 2000s, the National Higher School of Art of Bourges, a small town in central France where Magnan taught the subject Genresss, became an epicentre of the European queer movement. Among the theorists and artists that Magnan invited to her classes were Paul B. Preciado (Spain: 1970) and Shu Lea Cheang (Taiwan: 1954, a member of Paper Tiger TV since 1981).

Influenced by cyberpunk and the texts of VNS Matrix, Donna Haraway, Greg Bear and Judith Butler; Shu Lea Cheang’s work reflects on the potential of technology to build and destroy anatomical boundaries and gender constructions, opposing a notion of monolithic and hermetic sexuality. Her films raise questions about the corporatisation of the body and feelings, virality and the creation of related communities. During World Pride in Madrid in 2017, Shu Lea Cheang worked with various local transfeminist groups, migrant groups and queer activists in the production of a geolocated mobi-web series. Each episode takes place at a point in the city where a homo-transphobic attack has occurred and audiovisual content can only be accessed by going to the location with a mobile phone. Thus, the fictions of resistance proposed by Shu Lea Cheang collapse spatially and temporally with the ghost of a violent event, preventing the episode from being erased from the Madrid LGBT memory.

The first explicitly feminist and dissident texts made their entry into post-dictatorship Spain with the publication Vindicación Feminista (1976-1979). However, there was no lesbian audiovisual imaginary of a positive type prior to the nineties. We dragged up hundreds of images from previous years in which a woman’s body was represented either as hypersexualised and subordinate to men’s hetero-patriarchal gaze (permissiveness and the 1970s; viva the Transition!) or subject to National Catholic morality, dispossessed of any type of sexuality and choreographed according to the discipline and gestures of Franco’s military dictatorship. -I like to think of the connection between the Spanish initials of the Women’s Section, la Sección Femenina, and the progressions of the SF coupling (Speculative Fiction/ Science Fiction/ Speculative Feminism/ Speculative Fabulation), of the chance to revisit that repertoire of gestures and perverting them, stripping them of norms and narrating through them what is erased-.

For many of us females, immersed in an environment of bathing in T-shirts and a daily rosary, sport and gymnastics was a bodily liberation, an unknown ingredient that broke the monotony of teaching that was absurd and irrational. For those who were most addicted to nuns, by contrast, it was a real torment, a complex of physical inferiority that manifested itself in their inhibitory bodily clumsiness. Envy engulfed them when they saw the agility, the beautiful bodily expression of the female instructors and us, their fervent worshippers.

Carmen Alcaide, Vete y Ama, 2005

Sobretodo Diferentes (lesbians different above all) Lesbianas Sudando Deseo (lesbians sweating desire), Lesbianas Saliendo Domingos (lesbians on Sunday excursions), Lesbianas Sin Dinero (lesbians with no money), Lesbianas Suscitando Disorden (lesbians causing disorder)). Setting out from her photographic series, Virginia Villaplana (Paris: 1972) created “LSD Feedback” (1998), an experimental videoclip in which the works of this queer collective meet the ghost of writer, poet, activist and lesbian Lucía Sánchez Saornil (Spain: 1895-1970), the co-founder of Mujeres Libres. In its frames, Villaplana also references the early works of Barbara Hammer and Su Friedrich, while the photographs and fanzines of LSD themselves remind us of the work of the feminist conceptual artist Barbara Kruger (USA: 1945).

The bodies appearing reference other bodies and make them appear: the bodies that disappeared during the Civil War and the dictatorship, the bodies buried in anonymous graves and ditches, the female bodies moulded and made invisible by National Catholicism, the bodies punished for not adapting to the norms of sex and gender etc.

Maite Garbayo Maeztu, “Cuerpos que aparecen. Performance y feminismos en el tardofranquismo”.

Referenceability, in addition to generating community, has the timeless power to set and freeze gestures and bodies, making them, through reiteration or iterability [4], resistant to history. Referenceability is therefore the main weapon of sexually dissident anthropological cinema, either through the deconstruction of stereotypes, through the creation of specular relations between real or fictitious bodies remote in time, or through different homages that make plausible the existence and the need of a community that is supported in work and emotion and fights against being erased.

In “A/0 (Caso Céspedes)” (Cabello/Carceller, 2009-10), Alex, a youngster of indefinite gender, discovers in the historical character Elena/o de Céspedes (Spain: 1545) an alter ego (just as Dunye did with Richards) of his/her own identity, an identity that five hundred years later continues to be conflictive, made invisible and poorly represented. Elena/o de Céspedes was a male/female surgeon from Granada who, having been born as a woman, lived a large part of her life as a man, marrying a woman in the Catholic Church in sixteenth-century Spain. Elena/o ended up being tried by the Inquisition, which imposed on her, after a multitude of degrading medical examinations, a woman’s identity. In this film, Cabello/Carceller reflect on the cinematographic medium itself and its hegemonic politics of representation; they approach race in the construction of Spanish identity during the colonial period and its almost complete erasure in the generation of imaginaries (Elena/o was the child of a black slave), as well as the queerification of spaces and architecture through the insertion of non-normative bodies into the landscape. After working for a decade with Anglo-Saxon references, Cabello/Carceller revisit the history and faultlines of Spain, recovering references in the context of the south of Europe and highlighting, in comparison with previous works, the anthropological differences represented by constructing imaginaries from a geographically-situated perspective.

My aim with these notes on sexually dissident audiovisual anthropology is not to establish a complete historiography around the subject. Rather, it is to share the images and the filmmakers who have accompanied me over recent years in my artistic and curatorial practice, as well as in my aesthetic and narrative preferences. In them, I have often found the same frustration with the impossibility of reconstructing the narratives and imaginaries of non-hegemonic identities, as well as the different strategies to confront the absence of iconographies to be grasped in the construction of a non-normative imaginary. But, above all, I have found in them images that explain me, traverse me and touch me.

Notes

[1] In her book ” The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas” (p.19), Diana Taylor defines both terms in the following manner: ” (…) the repertoire consists of corporalised acts of transfer and the archive preserves and safeguards the printed and material culture – the objects.”

[2] I use the prefix “counter-” in relation to Paul B. Preciado’s “Countersexual Manifesto”, in which the term countersexual is defined as the rejection of normalising power structures that produce and promote thought about sexuality and gender from a patriarchal, heterosexist and capitalist context.

[3] “Posing is issuing a threat.” Craig Owens, “The Medusa Effect, or, the Spectacular Ruse,” in Beyond Recognition: Representation, Power and Culture, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1992, p. 192.

[4] In her book “Cuerpos que aparecen: performance y feminismos en el tardofranquismo” (p.21), Maite Garbayo refers to the Derridian term of iterability and explains it as follows: “The critical possibilities inherent to the performative are found in the notion of iterability, a term that Derrida proposes to emphasise the union between repetition and alterity. Iterability explains that every repetition always establishes a difference. All iteration, all parasitic use of the act or language, introduces a variable within the convention. The same act of speech is always open to the possibility of acquiring a different meaning. (Derrida, Jacques, “Signature, event and context”, in Márgenes de la filosofía, Ed. Cátedra, Madrid, 1998, pp. 347-372).

Quiela Nuc (Madrid, 1990) is an artist, curator, teacher and part of nucbeade. Her work, both individual and collective, shifts between documentary, performance and speculative fiction. She approaches identity from perspectives that are highly diverse but always subversive and inscribed in the margins of ferocious, anthropocentric and heteropatriarchal neoliberalism. She has curated audiovisual series and activities for La Casa Encendida, CA2M, Matadero Madrid and the Círculo de Bellas Artes. She has also given workshops and seminars at La Térmica, LENS School of Visual Arts, CCE in Santiago, Chile, 6th Festival Márgenes, the Master’s Degree in Public Orientation Anthropology of the Autonomous University of Madrid, the Carlos III University of Madrid and CA2M. Her works have been exhibited internationally in museums and galleries such as Kunstraum Kreuzberg Bethanien (Berlin); QueerTech.io, RMIT ART INTERSECT Spare Room (Melbourne); MELT Festival (Brisbane); Club Social de Artistas (Santiago, Chile); and La Neomudéjar, Sala de Arte Joven and Espositivo Gallery (Madrid).