Oct 2018

Over the strong nudity of truth

the diaphanous veil of fantasy

Eça de Queiróz

The phrase “anthropological cinema” is both tautology and oxymoron. Confusion persists, semantic incongruity makes it credible. Cinema is as anthropological as a footprint in clay earth. Traces of humans do not assure a greater knowledge of them. However, in a post-truth world, cinema’s sole opportunity is to be anthropological as a manner of guaranteeing the reality of imagination. A stronghold of the resistance of humans in the world(s) in the interior, exterior, vegetable, animal, mineral, sidereal universe(s) etc., the anthropological is the human but is also everything that coexists with the human: the wind, the rain, the rocks, large vertebrates, fungi, bacteria, phantasmagoria, etc.

We live in imagined (but not imaginary) worlds, we use our personal imagination, as well as collective imaginaries, to represent our worlds and attribute meanings to them.

Noel Salazar.

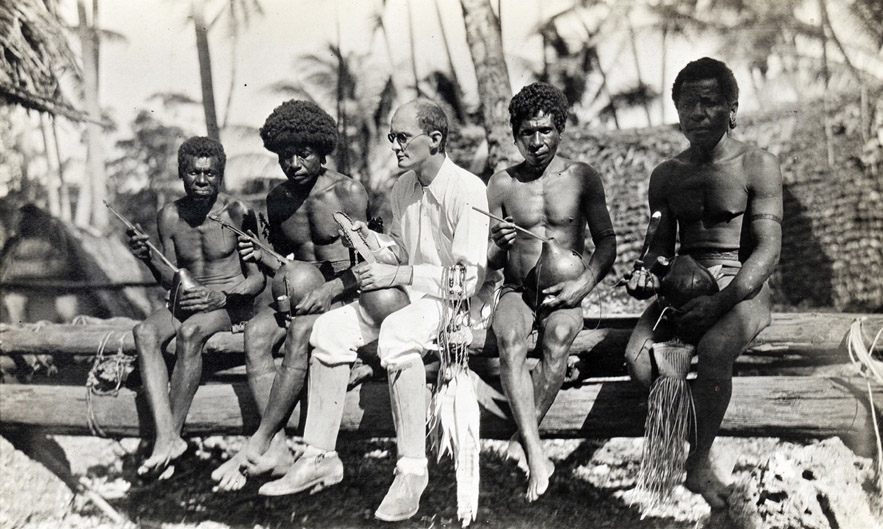

What characterizes anthropological cinema? Why should “Nanook” be more anthropological than “Dr. Mabuse”? Why should the images of a female Wolof potter chronophotographed by Felix-Louis Regnault be considered ethnographic and not the moving images, their contemporaries, of a train’s arrival at the station presented by Lumière? Why is someone who is born in the Amazon jungle more ethnographic than someone born in Madrid? The idea of the relation of ethnography to what is non-familiar runs counter to the aim of anthropology to consider the senses of human experience, whether on board a space station, in the Amazon jungle or in a suburban cafe.

Friction: A young Guarani woman posts on Facebook a cover of a Beyoncé song; an ageing New Ager, Swedish perhaps, shares on YouTube a tutorial on the procedure for carrying out a shamanic ceremony.

Why do we still insist on sterile categories that lack meaning? Not only that, we blithely exchange categories by terming certain filmic objects ethnographic or anthropological, as if such definitions were synonymous. On the one hand, we want to free ourselves from the ghosts of colonialism but we resort to the same concepts, practices and worldviews that created them. What distinguishes ghosts from the living is precisely the fact that the former are now dead, hence the difficulty of making them disappear; we have to learn to live with their presence and take them seriously but this should not lead us to imitate them.

Does the specificity of anthropological cinema lie in its collaborative dimension? In its reflexivity? In a relationship committed to reality? In the representation of human cultural diversity? In prolonged immersion within the filmed community? In the ethical and responsible transparency of the ethnographic encounter?

The journey as domination

One of the specificities of a cinema termed ethnographic or anthropological may lie in the extreme mobility of those who claim to practice it in the face of the precarious (im)mobility of “their” filmic subjects. The union between cinematographic, touristic and ethnographic practices is not an innocent one. Cosmopolitan mobility has transcended these three practices, ever since its origins and up to our time. Anyone who intends to make a film with an ethnographic tradition, however thoughtful and critical it might be, will in most cases travel and gain access to realities that are distant to them, with the financial support of civilized institutions. Such access is rarely granted by a reciprocity agreement: negotiation and intrusion in certain worlds is anchored in economic and political processes always involving power relationships and dynamics between centres and peripheries that are overshadowed by colonialism.

The creators of these films are beings in movement, privileged social actors (cosmopolitan connoisseurs), who gravitate from “their” shoot locations towards festivals around the world, between their visits to universities, art galleries, and their return to homes in gentrified neighbourhoods in the capital. The nature of their movements is physical, but also social, insofar as they cross social hierarchies by ignoring the contradictions they help to perpetuate. These contradictions are often legitimized by the imperative of “publicising”, of “translating”, certain situations for a “Western” audience, or by the way in which their creative and critical individuality can convert the world’s complexity into filmic products. Dennis O’Rourke rejects the role that establishes the filmmaker as a cultural hero, someone who aims to be a traveller, but who is hardly more than an informed tourist, one who demonstrates scant aesthetic and moral sense. We cannot continue to deny that tourism is a central element of contemporary cinematographic practices. This we can verify in the resurgence of the essayistic travelogue in photochemical format. The illusory Abyssinian ethno-ambitions of the Rimbauds of the 21st century are manifestations of the same circumstances that originated geographic exploitation and imperialism. The film director who is “inspired ethnographically”, just like the tourist or the anthropologist, is a marginal creature who temporarily inhabits another culture and who portrays it for domestic, academic or artistic consumption. Cinema, tourism and ethnography are more related to what we imagine that the other is than what he or she really is. For Edward Bruner, tourism is just a further form of representation, whose privileged sensory medium for the perception of the “native” is through the viewfinder.

Cinema will always be a form of anthropological expression

“The uncertainty principle: What we know of the world depends on how we interact with it. Our methods and personalities alter and partially constitute the nature of what we observe.”

Werner Heisenberg

Lucien Taylor considers opacity and resistance to semiotic explanation and decoding as a singularity of anthropological cinema. This view is shared by David MacDougall, who trusts in the possibilities of cinema as a sort of commensal relationship with the world and not so much as a unilateral act of communication that places explanation above experience. Cinema is a medium that favours subjectivity and human experience. Ethnography is born out of the positivist aspiration of making scientific the gathering of data related to human activity.

The use of cinema as a positivist data-gathering instrument is to ethnography what the use of cinema as a means of expression is to anthropology. For Margaret Mead, the camera should be used to collect ethnographic data. She believes that the resulting audiovisual sequences should have an exclusively scientific purpose. Her panoptic utopia aimed to nullify the selective, the subjective and the impressionistic for the sake of guaranteeing the accuracy of the “ethnographic reality” for later analysis (we can picture Margaret Mead, with access to 360 degree cameras, drones, photogrammetry, etc., reproducing Balinese hamlets in virtual reality environments). For Bateson, cinema and photography are forms of artistic expression and not exclusively scientific instruments for data collection. In the famous debate between Mead and Bateson about the use of the camera in anthropology, we get a sense of the difference between ethnography and anthropology recently raised by Tim Ingold.

Ingold tries to clarify two practices that, while complementary, are not sides of the same coin and whose aims are clearly different. Ethnography attempts to describe life as it is lived and experienced by people at a certain time and place. Anthropology, on the other hand, is a questioning of the conditions and possibilities of human life in the world. Ethnography seeks, above all, to collect information in a contextualized manner with a maximum attention to detail, through writing, images and sounds. It is always conditioned by descriptive accuracy: it must reflect the other in the most analytical and objective way possible. Anthropology, meanwhile, must always be critical and speculative, born out of each person’s critical reflections, and it does not seek to be authoritarian. This difference and distinction between ethnography and anthropology frees anthropology for other forms of research through various artistic practices, cinema, drawing, theatre, dance, music etc. For this thinker, the attempt to combine ethnography with artistic practices always leads to bad results because they invariably compromise both the ethnographic aim of reliable description and the interventional and experimental interrogation processes that characterize the artistic process. However, an anthropology that is experimental and interrogative can produce extremely productive results when combined with artistic practices.

What is crucial about both anthropology and art practice, and what distinguishes both from ethnography and art history, is that they are not about understanding actions and works by embedding them in context—not about accounting for them, ticking them off, and laying them to rest—but about bringing them into presence so that we can address them, and answer to them, directly.

Tim Ingold

(im) possibilities

A visual anthropology – audiovisual, sensory – is much more than an ethnographic film but it appears that the latter continues to dominate common understanding of this subdiscipline. Anthropologists such as Anna Grimshaw, Amanda Ravetz and Sarah Pink have attempted through their texts and practices to demonstrate the potential of the use of audiovisual technologies in anthropological research far beyond the mere making of ethnographic films. Ironically, the ethnographic film appears to resurface in the artistic and cinematographic media, largely due to the Sensory Ethnographic Lab but also to a need to legitimize artistic practices theoretically. Increasingly, adorned with academic jargon and imbued with a near encyclopaedic imperative of documentation, we hear about visual artists who have explored a certain topic ethnographically, or who have used an archaeological method in their creative processes. An artist no longer creates but researches, which appears a more serious activity. At the same time, increasingly more anthropologists, disillusioned with the corporatist and economicist dynamics of academia, attempt to move closer to artistic practices.

It may be only a matter of categorization, of binary oppositions that we still cannot transcend: art/science, we/others, fiction/reality, indigenous/foreign, pure/hybrid. While we may not know how to deal with these new ways of being in the world, we continue rescuing nomenclatures or suggesting hybrids, contaminations, etc. In the end, all of us need to be paid and almost all audiovisual projects, whether they be academic or artistic, require the written word in order to be accepted, in order to demonstrate what images are to be used for.

After the death of a member of the Warlpiri, women from his family group go through the camp with eucalyptus branches to sweep the tracks of the deceased, erasing any trace of his presence. Thus, the deceased loses his unique identity and enters ancestral time as a spirit. We prefer to delay the destruction of our traces with images, thereby negating the possibility of transcendence.

Errare cinetographicum est…

Gonçalo Mota studied anthropology and cinema. As a researcher, he works with audiovisual archives related to touristic practices and representations and on the use of drones and virtual reality in the touristic promotion of the landscape of the Douro Valley. He formed part of the organization of Anamnesis: Encuentro de Cine, Sonido y Tradición Oral de Trás-os-Montes (Anamnesis: Meeting of the Film, Sound and Oral Tradition of Trás-os-Montes) (2007/12) and Encuentros de Primavera en Miranda do Douro – Antropología, Cine y Sentidos) (Spring Encounters in Miranda do Douro – Anthropology, Cinema and Senses) (2005/18). He was responsible for the sound of the films Revolution Industrial (2014) by Tiago Hespanha and Frederico Lobo and Anteu (2018) by João Vladimiro. He collaborates regularly by integrating video into the works of the theatre and dance company Circolando (http://circolando.com/) and the project LOA by Lucifer’s Ensemble (http://www.lucifersensemble.org/).